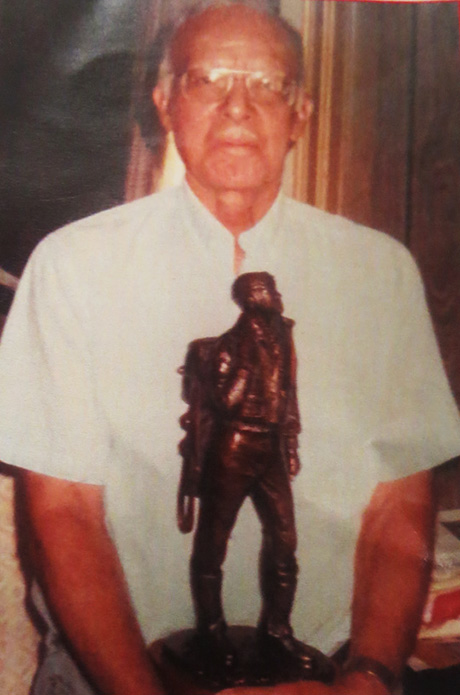

Nicholas Stewart Neblett was one of the 1,000 members of the distinguished Tuskegee Airmen, the first black men to serve the U.S. during World War II.

Dale Neblett, a senior vehicle mechanic for Duke Energy in Cincinnati, knew his father as a good man and a war hero.

“Dad was proud to be a Tuskeegee Airman. He and my mom went to the annual convention every year until she passed away,” said Neblett. “But what he was most proud of was being able to provide for his family. With so many mouths to feed, we never had much, but always had our needs met.”

When Neblett died at age 93 in late 2014, he was one of the last remaining Airmen. It wasn’t easy for him and his colleagues in the military.

Many doubted – and even resisted – the idea of African-Americans serving as military pilots. Known as the Tuskegee Airmen Experience, the first black pilots were trained at a segregated air base in Tuskegee, Ala., in 1941.

Neblet was 23 when drafted into the Army in 1943. With no aviation training but a love of planes and unending perseverance, he applied for and passed rigorous tests to enter the Army Air Corp Cadet program.

He never spoke of discrimination or let bitterness rob him of the present.

War experiences

“Dad was one of a handful of Tuskegee Airmen who graduated as a bombardier, navigator and pilot,” said Neblett. “Growing up near Lunken Airport, he watched the planes land and attended air shows that featured Jimmy Doolittle. I think it was his love of flight and ability to work with his hands that made him successful.”

Though he never flew overseas, he faced racial hurdles while in the military.

“At the Tuskegee base, the black pilots had to land planes in corn fields while white pilots used blacktop and concrete airstrips,” said Neblett. “Dad said it only made them stronger by dealing with the difficult conditions.”

But needing to prove himself wasn’t limited to white airmen as some black pilots also raised obstacles.

“Dad was assigned as a co-pilot to another black pilot who had experience flying twin engine planes. Having only single-engine experience, he gave my dad a hard time.

“But when they were flying the Tuskegee football team to D.C. and dropped out of a 12-plane formation due to heavy fog, my dad earned his respect by safely navigating the flight to Bolling Air Field. In fact, they landed third out of the 12 planes.”

Neblett was passed over for many promotions by white cadets who served less time, but eventually attained commissioned officer status of first lieutenant due to his stellar performance.

Life post war

After the war, Neblett worked as a truck driver for the City of Cincinnati and then the Post Office. In 1950, he was hired at GE as a janitor and eventually worked his way up to foreman in the jet fighter test department. He stayed at GE for 32 years. Neblett was married to Felicia and they had seven children – one a daughter. He loved baseball, often going to Reds games at Crosley Field.

Passing on a legacy

Neblett summed up his thoughts about his dad:

“Memories of dad are that he was always around for us and that he absolutely meant what he said. At the dinner table, he never spoke of discrimination or let bitterness rob him of the present. Because of that, we have that same outlook on life. Yes, there were many injustices in the past, but you can’t let that keep you down. You learn from it and work to make things better.”